The Helsinki basic education curriculum also includes practising participation skills at school. OmaStadi provides a smooth way to learn the skills of participation and empowerment. At its best, it gives children and young people a positive feeling that social participation pays off.

The playground, known as Tuhkimo (Cinderella), is located in a green park area sheltered by two hills. It is also known as the pearl of Roihuvuori village’s Japanese-inspired Hanami festival. This is one of the images that many people in Roihuvuori associate with Tuhkimo playground, whose proposal for restoration received 1,477 votes in the second OmaStadi round – the most in the entire eastern metropolitan area.

The idea was the brainchild of the Porolahti Primary School pupils’ association and the Roihuvuori Association. They had not worked together before, but the shared dream of improving the playground, that was important to all of them, triggered the collaboration.

In addition to the pupils' association and the Roihuvuori Association, one resident had also proposed a similar idea in OmaStadi. All those who submitted ideas met in an OmaStadi workshop. Three similar ideas were transformed into one common proposal.

One reason for the success of the proposal may be that the playground is popular with children and young people. There are schools on both sides of it. “During the day, the playground is visited by day-care centres in the area,” says Otto-Ville Mikkelä, Executive Director of the Roihuvuori Association.

Tuhkimo playground’s story has been more than just dancing with roses. Maintaining and revitalising it has taken much effort from local residents, especially in recent years.

The city stopped playground activity in Tuhkimo park, after which some parents in the area ran a playground on their own initiative. Others sold juice in the part of the playground building, while others froze the park’s sandy pitch into a skating rink in the winter.

Participatory budgeting provides an opportunity to teach empowerment, advocacy and decision-making

The local parents, however, were not the only ones with dreams and plans for Tuhkimo playground.

Last year, the teacher who runs the pupils’ association at Porolahti Primary School, Petra Ivars was wondering how to teach the pupils how to make decisions, influence and promote common issues through experience and action.

After the first OmaStadi round, Ivars felt that, in addition to voting, participation and empowerment could also be taught by helping pupils to develop their own proposal for OmaStadi.

“Some of the pupils went for a walk with their teacher to see what could be changed or improved in their local environment to make it more comfortable and functional,” Ivars says

After their walks, the pupils discussed their ideas together. The ideas were then voted on and the proposal with the most votes was recorded in OmaStadi in the name of the pupils’ association. The pupils were also asked to write down other suggestions in OmaStadi in their own names. Among primary school pupils, the restoration of Tuhkimo playground received the most support. Pupils in the secondary school age group, on the other hand, submitted a proposal to improve their school playground.

Alba, Hilda, Aamu and Kerttu were involved in developing a proposal from Porolahti Primary School for the restoration of Tuhkimo playground. In their opinion, the park was nice and busy, they but they said its condition was a bit disappointing, especially compared to the nearby cherry orchard and Japanese garden.

“It would be nice if this could finally be done now. It would be great if we could come here as adults and think, hey, we did this and that,” the pupils reflected.

In the pupil’s opinion, the brainstorming for the OmaStadi proposal and the development of the ideas was more difficult than they had originally thought. Not least because the proposal was first rejected before being approved. Upon further review of the proposal, the city later stated that it could still be implemented.

For a common cause

When the voting started, Roihuvuori Association and the pupils of Porolahti Primary School campaigned together and separately for their own proposals. According to Mikkelä, Roihuvuori is a networked district. It was therefore easy to get the local residents to promote a common cause.

The campaign used a Facebook group, Roihuvuori Association's mailing list, the school’s online service Wilma and posters made by the pupils. The posters were put up on notice boards in the Porolahti and Roihuvuori districts. The campaign period was very short as information about the proposal was only received two weeks before voting was due to start.

“Fortunately, there was enough time!” say Ivars and Mikkelä.

OmaStadi is for Helsinki residents

OmaStadi is Helsinki's way of implementing participatory budgeting. Helsinki is spending €8.8 million to turn citizen’s ideas into reality. Together, these ideas are developed into proposals that are then voted on by the citizens. The city implements the proposals that receive the most votes.

In the second OmaStadi round (2020–2021), 1,463 ideas were submitted to make the city more welcoming and functional. In October last year, 397 proposals were put to the vote and 75 were put forward for implementation.

Read more:

Tuhkimo playground(Link leads to external service)

OmaStadi(Link leads to external service)

Find your(Link leads to external service) own way to participate and influence the development of Helsinki(Link leads to external service)

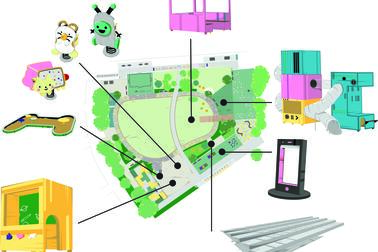

Drawing: Minna Alanko, City of Helsinki material bank.

Photographs: Kimmo Brandt, City of Helsinki material bank.