Number of series

Series are for example lines in a line chart, slices in a pie and donut chart, and elements coloured with the same fill colour in other charts types – e.g. as in the clustered column chart.

Limiting the number of series simplifies and clarifies a chart in the same way that using short and clear sentences clarifies text.

In the most common chart types, you should usually limit the number of series to a maximum of six or seven. When visualising more series than this, you run into the problem of finding distinctive enough colours for each series, not to mention that the chart becomes very complex.

A chart with a larger number of series can be split into a small multiples display. Another option is to combine some of the smaller series: for example, in a chart showing housing types, single-family, semi-detached and terraced houses can be grouped together and this series can be named “small houses.”

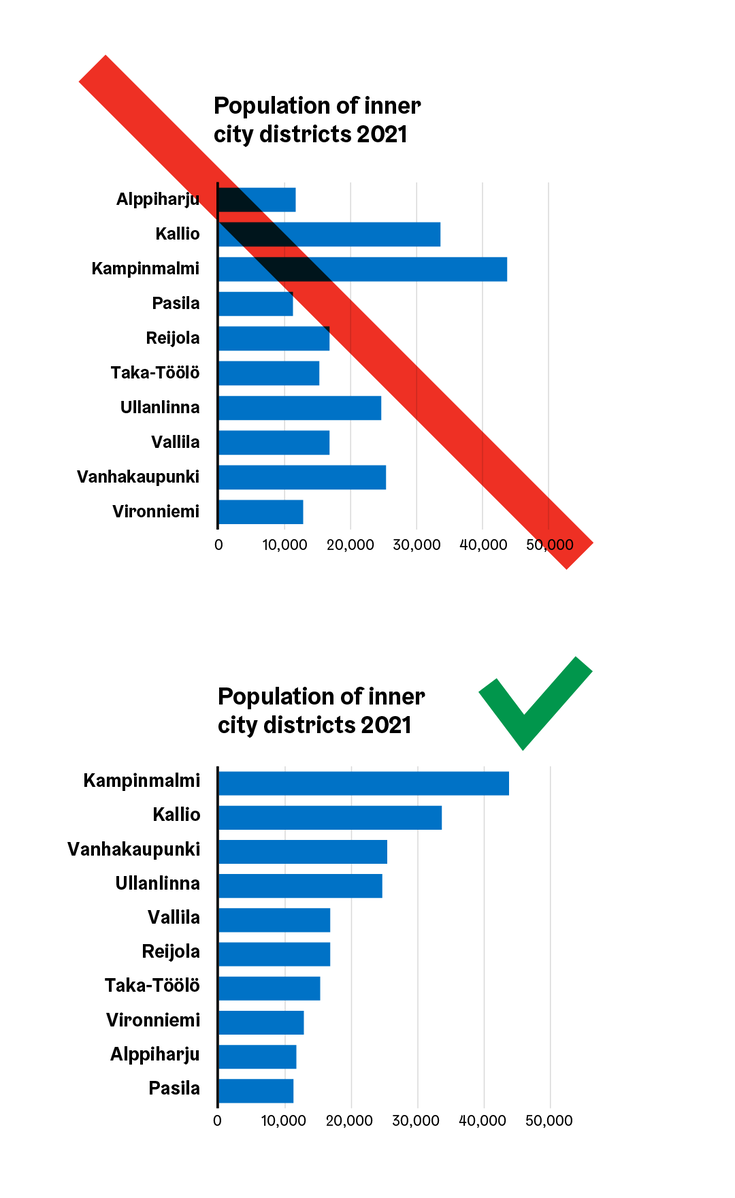

Element order

In many chart types, the sequence of the elements cannot and may not be rearranged: for example, in a line chart, time runs from left to right and the series arrange themselves vertically according to the magnitude of the values. In some other cases, the information is placed naturally in a certain order – for example, income brackets are set in order of magnitude, and Likert scale values (completely agree, somewhat much agree… etc.) are arranged progressively from one extreme to the other.

In many cases, however, the chart type or the axis scale used do not dictate the order of the elements themselves, but you can choose the order yourself from many different options. In such cases your choice of arrangement can have great influence over the chart’s message.

The chosen order should tell something about the dataset’s characteristics. Alphabetical order or other subjective ordering such as e.g. the order of elements as they appear in the the state budget, do not reveal anything interesting about the material, so it is not recommended for use in visualisations. (Alphabetical order is however well suited to tables.)

In chart types where the order can be chosen freely (e.g. horizontal bar chart) the most commonly used organizing principle is an order of magnitude. Ordering from largest to smallest in this way has many advantages: you can quickly identify e.g. which is the largest and which is the smallest value, and ascertain the general size groups contained within the data.

If there are several series in the chart, you have to consider which of them would be used as the basis of the order of magnitude. In stacked bar charts the order is usually formed based on the total sum of the series.

If there are several charts that are related to each other in terms of content, the order may vary from chart to chart. However, it would be preferable if the order remained the same in charts intended for comparison. Usually the solution is to choose the first or most important of the charts, arrange it in order of magnitude by a chosen series, and use the same order in other charts.

Along with the order of magnitude, other frequently used organizing principles are chronological order, order by location (e.g. from north to south) and categorical order where items belonging to the same category are listed consecutively.

In pie and donut charts, you should usually arrange the slices in order of magnitude so that the two largest slices are in the top center, which is the most prominent and visually “valuable” place in the chart. For example, in Excel, this is done most easily by arranging the slices in order of magnitude first, followed by moving the largest slice last.

Any possible “other” slice should always be drawn last, even if its slice size would usually place it elsewhere in the order.

This is not an absolute rule, so depending on the content of the chart some other order may be justified.

Gridlines and baselines

Gridlines refers to the background lines of a chart which denote the scale interval, and enable the precise reading of data points as well as comparison between them. The gridlines should not compete for attention with the actual content of the chart, but should just barely stand out from the background.

Gridlines can be vertical or horizontal. In most chart types only one of these is usually used: in a horizontal bar charts a vertical gridline, while in most other charts horizontal gridlines are used. Some chart types such as scatter plots and bubble plots (which are not covered in this guide) use both.

Gridlines are not necessarily needed in simple bar/column charts or in slope graphs at all , in which case the alternative to gridlines is to write out the individual values as labels directly on the columns (or next to the data points in the slope graph).

The baseline is the zero level of the chart – or when visualizing indices, index number 100 – and is usually drawn with a darker and thicker line than the gridlines.

Series and data point markers

Markers are elements used in line charts, dot maps and some other chart types (which are not covered in this guide), the purpose of which is to help distinguish between data points belonging to different series. They are usually simple geometric shapes such as circles, triangles, and squares.

The markers for different series don’t necessarily have to be different shapes, and especially in the line chart it is even desirable to use only symbols of the same shape in different colours – usually these are circles, because the round shape stands out better from the angular series line.

More variety can be brought to the marker symbols by using an outline, e.g. combining coloured symbols alongside ones with a white fill and coloured outline.

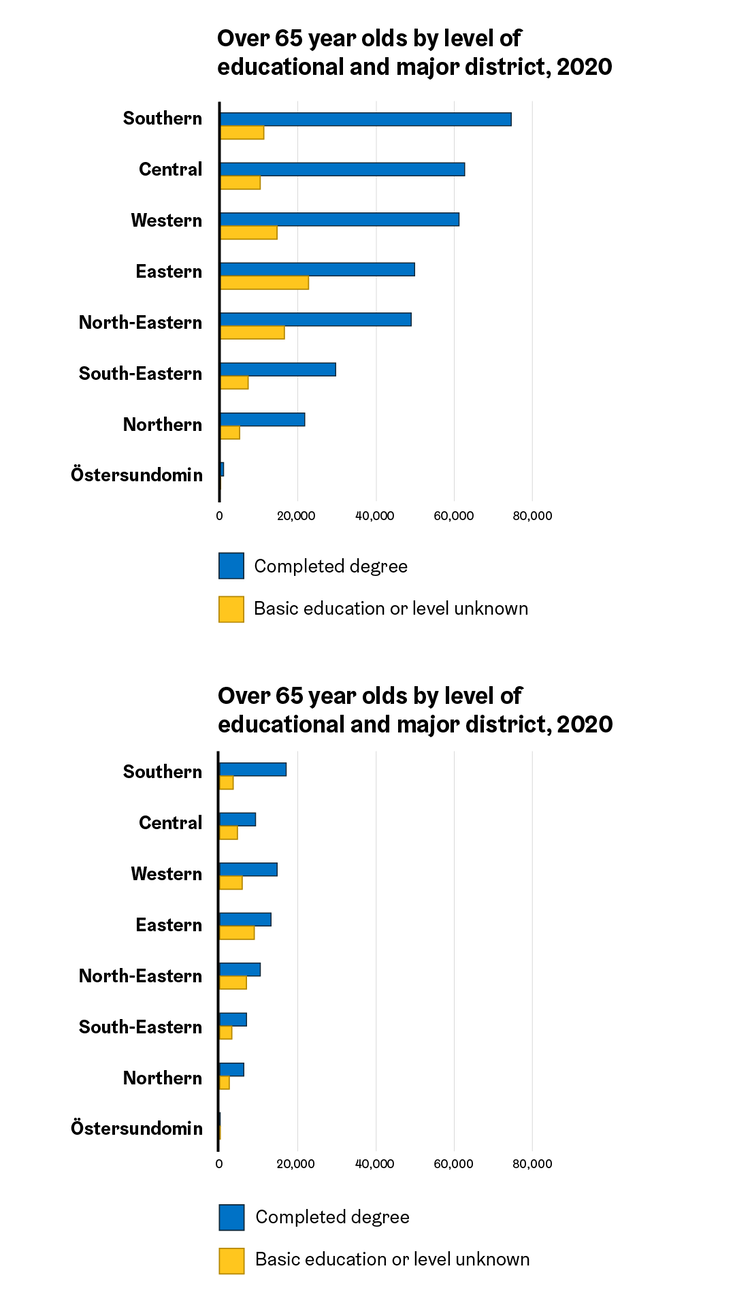

Consistent axis scale

When closely related charts that have the same unit of measure are presented in the same context, for example the same website or in the same printed publication, it is preferable to use the same axis scale on all, so that visual comparison between charts is possible.

If for some reason it is nevertheless deemed necessary to show related charts using different scales, try to make the charts clearly visually different from each other, e.g. by using different chart types so that the reader does not try to accidentally compare the two charts together.

Axis truncation

Axis truncation – that is, using an axis scale that does not start from zero – is strictly prohibited when using column or area charts, or other chart types in which chart elements begin from the baseline, as this would distort the shape and size of the chart elements.

In chart types where elements don’t extend to the baseline, nor does their shape get distorted by cutting off the scale – e.g. a line chart – scale truncation is allowed if it clarifies the chart overall. However, do note that if the zero level is not visible, absolute comparison of data points is not possible. So you can’t for example use the chart to say that a value has doubled, but only to estimate how the rate of change has developed.

If the scale is truncated, it should always be clearly marked, for example with a marker drawn on the edge of the axis. Also remember to replace a darker baseline with a plain, lighter gridline.

Text elements

All texts that are necessary for understanding the chart should be included directly in the chart itself. This ensures that essential information is not lost if the chart is cited outside of the original context.

Text elements usually include:

- Title and possible subtitle

- Axis title, if the unit used does not already appear in the title or subtitle

- Series or data point labels

- Data source if it is not apparent from the title or context

- Highlights and comments, which draw the reader’s attention to interesting features or explain surprising phenomena

You should always try to keep all text in the chart horizontal, as the readability of horizontal text is significantly better than text written at a 45 degree angle, or vertically.

If the text elements in the chart do not seem to fit in place horizontally, you should e.g. consider replacing a vertical column chart with a horizontal bar chart, or thinning the labels of the time series so that only some of the labels are displayed.

Titles

The chart should usually have a main title. It can be neutrally descriptive (e.g. “District heating by energy source”), but an increasingly common practice is to title figures in a “journalistic” style. In this case, the title of the figure imparts some key takeaway (e.g. “The share of renewable energy grows in district heat production”) in the same way as the title of a good newspaper article.

With a well-chosen journalistic headline, which is sometimes also described as say what you see, the title entices the audience to read the chart, and also helps them to evaluate whether the interpretation of the data is correct: if the reader observes in the figure the same key points as those offered in the title, it confirms that they have understood the chart correctly.

A subtitle is usually used in addition to the journalistic title, and tells the reader other key information for understanding the chart, such as geographical, temporal or categorical information.

If the unit of measurement does not appear in the main title or subheading, it should be displayed as a separate axis title, unless of course the unit used is self-explanatory such as a series of years.

Series or data point labels

The information-bearing elements of the chart are usually labeled either with a separate legend or direct labeling. In a simple column chart, the columns are preferably always labeled directly, while the colour scale of a choropleth map requires a separate legend. Other chart types though, for example the series in a line chart or stacked column chart, or the slices of a pie chart, can be labeled either way.

It is not necessary to repeat the names of the series of a stacked column chart in every column; it is enough that each colour is labeled once, as in the example below.

If direct labeling is used in the line or pie chart, you don’t necessarily need to give each series its own identifying colour. In addition, a label directly connected to its series or slice can be assessed faster and easier than one in a separate colour legend.

When using direct labeling, you can choose the chart colours more freely, because the selected shades do not necessarily have to form a completely accessible whole. This is because when using direct labeling, the chart is easily readable even in the event that a difference in colour vision prevents differentiating the shades from each other. (Accessibility requirement compliant contrast levels must still be met in this case as well, so that the chart elements stand out sufficiently from each other and from the background colour).

In addition to series, individual data points can also be labeled directly, if there are a reasonably small number of them. This is especially used in horizontal bar charts. The label is placed inside the column so that the text next to the column does not make it difficult to accurately assess the height of the column.

If the data points of a bar or column chart are labeled, gridlines may be left out.

Other texts

In addition to titles, labels and legends, charts may contain at least axis titles, data source information, and highlights or comments.

Axis titles are used when the unit of measure is not apparent from the title or subtitle, and is not self-evident such as a series of years.

It is good practice to mark the data source, when it is not similarly obvious from the title or from the publication context.

Highlights and comments can be used to explain or draw the reader’s attention to surprising or otherwise noteworthy features, such as e.g. change of measurement method or definition in the middle of the time series.

A highlight or comment box is usually connected to the feature itself with an arrow. For this purpose it is better to use a curved arrow, as it stands out better than a straight line.